|

P-38 Glacier GirlOf the 9,942 P-38 Lightnings produced, Glacier Girl has drawn most of the attention. It isn’t because she was built different than the others, or because she survived some famous air battle. It’s because she survived 50 years of being buried under 268 feet of ice in Greenland. Before we get to the story of Glacier Girl, a little background is in order. P-38 Lightning BackgroundThe P-38 Lightning was the brainchild of Lockheed’s Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson, one of the most ingenious aircraft designers in aviation history. When the US Army Air Corps put out a request in 1937 for a high altitude interceptor capable of 360 mph at 20,000 feet, Johnson responded with the Lockheed Model 22 - a twin engine, twin boom design, which would later be designated the XP-38 in prototype form. The Model 22 was very similar in design to the German Fokker G.I. On January 27, 1939, the XP-38 prototype took to the air and exceeded expectations. It outperformed frontline fighters of the day, the P-39 Airacobra and P-40 Warhawk. The XP-38 was faster, had better range, and a much higher rate of climb. At the insistence of USAAC commander General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold, the XP-38 set out on a transcontinental flight in February, 1939. It covered the distance in seven hours, two minutes, including two fuel stops, and was a record at the time. Despite this amazing feat, the aircraft crash landed in New York when the pilot landed short of the runway. This set the program back two years, but based on the cross-country flight alone, the Air Corps ordered 13 aircraft, now designated the YP-38. See photo below, courtesy USAF.

After two years of production problems, design problems, and politics, the first combat ready P-38E rolled off the assembly line in October, 1941, followed in April, 1942, by the P-38F. Besides the US, England and France had also ordered the P-38F. General Hap Arnold was concerned about ferrying aircraft safely to Europe, so he devised a plan called Operation Bolero. The plan called for a northern route that would take aircraft from the US to Canada, Greenland, Iceland, and on to England. The JourneyOn July 15, 1942, six P-38s and two B-17s left Greenland on the third leg of their ferrying trip bound for Iceland. Off the eastern coast of Greenland, the flight ran into bad weather and it was decided to abort this leg and turn back to Greenland. As the aircraft approached the eastern coast of Greenland, they encountered worse weather, yet they pressed on, hoping to get back to the base on the western coast of Greenland, but a navigational error on the B-17 put the flight way off course. After eight hours of flying time, they wound up on Greenland’s east coast, and never came near their base. Because of dwindling fuel, they had to make emergency landings.

The first to land was section leader Lt. McManus who tried to land with gear up. Unfortunately, the terrain was filled with many crevices and the landing proved rough. On final approach, his engines froze up, and the aircraft flipped over. He had to be dug out, but injuries were minor. The rest of the flight, including the B-17, all bellied in with no problems. All the flight members were rescued two days later thanks to the B-17 radio operator sending out distress signals prior to the emergency landing. The seven aircraft would become distant memories as time passed. The SearchStarting in 1977, twelve different teams tried to locate and recover the aircraft. It took more than money and desire to accomplish this daunting challenge - it took technology. The turning point came in 1988 when the Greenland Expedition Society (GES) located the squadron with an ice scope. Shifting ice patterns had taken the planes three miles from their original location. A steam probe penetrated the ice for confirmation. Depth was 250 feet.

In 1990, the crew returned with a thermal meltdown generator, and the device steamed a four foot diameter hole in the ice. A workman was lowered down the hole with a hot water hose to clear away the accumulated ice from the B-17 called ‘Big Stoop’ (41-9101). Water was pumped out and up to the surface. Unfortunately the Flying Fortress was completely crushed, so they turned their attention to the P-38s. The RecoveryThe Lightning that was closest to the bored hole appeared to be in reasonable enough shape for restoration, but how do you get it out? You first have to free up the area around the aircraft which was done very slowly and meticulously. Imagine being in a flooded basement during a cold winter and having ice chunks fall on your head wondering whether you’re about to be buried alive. The workers faced that every day. When it was deemed safe enough, the aircraft was taken apart, and each piece was hauled to the surface, identified, and logged. In order to lift the three ton center section to the surface, the shaft had to be widened and a specially manually-operated hoist was erected. It took two days to inch the heavy section to the surface. Once all the parts were returned to the US, it was discovered that the P-38 had suffered more damage than originally thought, but much of the hardware was salvageable. The items that could not be used became templates to generate new parts.

Many organizations and countless numbers of volunteers put the Humpty Dumpty aircraft back together again. It took nine years to transform crushed and twisted metal into a diamond of an airplane named ‘Glacier Girl’. And what a jewel she is. She flew again on October 26, 2002, with one of the best pilots in the business at the controls - Steve Hinton. The 20,000 people in attendance were enamored at the sight of a dead diva brought back to life. Glacier Girl Notes- It is estimated that the Glacier Girl project costs $6.9 million. - One of our good friends, Joe Meyers, has established a non-profit organization dedicated to the recovery and restoration of the remaining five P-38s and the two B-17s. If you would like more information, please check out the website,

www.operationbolero.org

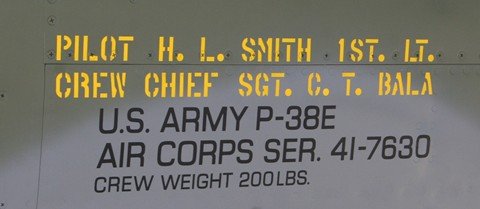

- The other B-17 buried in the ice is named ‘Do Do’, and has the USAAC number 41-9105. Air Show PhotosI've seen Glacier Girl four times since 2003. Here are some of the photos. This first photo was taken by our ace photographer and all around good guy, Horace Sagnor, at the 2006 Aviation Nation show at Nellis AFB. It's a rare event with five different World War II vintage aircraft in formation. From top to bottom are: TB-25N Mitchell 'Executive Sweet' (44-30801A, N30801) P-38F Lightning 'Glacier Girl' (41-7630, N17630) TF-51D Mustang 'Tempus Fugit' (44-63865, NL151TF) FG-1D Corsair (92106, NX106FG) F8F-2 Bearcat (122674, N7825C)

The next two photos were taken at the 2006 Planes of Fame airshow in Chino, CA. First up is the USAF Heritage Flight with Glacier Girl surrounded by an F-15E Strike Eagle (89-0492) and a F-51D Cavalier Mustang 'Six-Shooter' (67-22580 marked as 44-22580, N2580). This is followed by Glacier Girl pairing up with another Lightning, a P-38L (44-26981, NL7723C).

Navigation IndexReturn to the top of this Glacier Girl page

|